Gas Giant

A Gas Giant (in the broadest definition) is an extremely large planet, primarily composed of gases, and usually with an extensive atmosphere of hydrogen and hydrogen compounds. They are technically subdivided into the following two primary classifications based upon their place of formation and overall chemical composition:

- Ice Giants, which form and tend to reside in colder regions of a star system.

- Gas Giants, which can be found almost anywhere.

Description (Specifications)[edit]

The broad term "Gas Giant" contains the following two primary subdivisions based upon their place of formation and overall chemical composition:

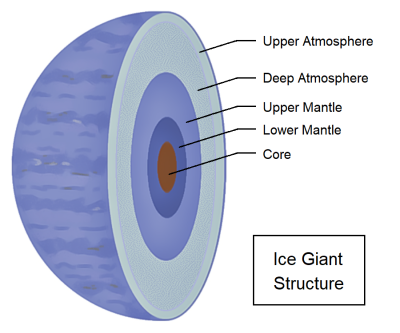

- Ice Giants, composed mostly of "ices" (i.e. chemical compounds containing hydrogen such as methane and ammonia) in the lower atmosphere, with hydrogen and traces of helium dominating in the upper atmosphere, are believed to form primarily within the colder regions of a star system beyond the snow line, and tend to be included with gas giant bodies that would typically be considered to fall into the "Small Gas Giant" size range.

- » The planets Uranus and Neptune in the Sol system are both considered to be examples of Ice Giants.

- Gas Giants proper are composed almost entirely of Hydrogen and some Helium gas, becoming liquid and eventually metallic liquid as the core is approached and the pressure is extreme enough to cause the electron orbitals of the atoms and molecules to collapse, forming a core upheld by quantum degeneracy pressure.

- » The planets Jupiter and Saturn in the Sol system are both examples of Class I Gas Giants (see below).

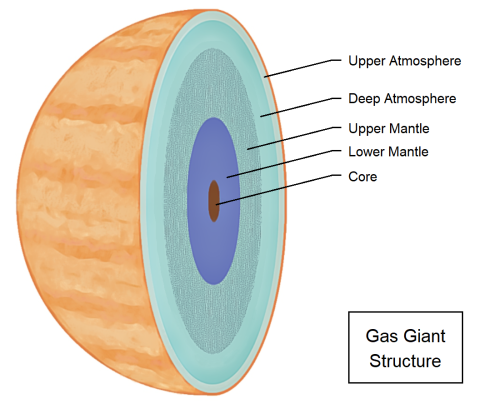

Structurally, gas giants may have a rocky or metallic core — in fact, such a core is thought to be required for a gas giant to form — but the majority of its mass is in the form of gaseous hydrogen and helium, with traces of water, methane, ammonia, and other hydrogen compounds (in the case of true gas giants), or in the form of various hydrogen "ices" (water, methane, ammonia, etc, with smaller amounts of hydrogen and helium in the upper levels) in the case of the ice giants.

Planetary Characteristics[edit]

Gas giants do not have a well-defined surface; their atmospheres gradually become denser and hotter toward the rocky core, with hydrogen in solid, liquid, or liquid-like states beneath the mantle layers.

- The deep interior regions may be composed of degenerate matter with collapsed electron orbitals, giving rise to exotic states of matter such as superfluid metallic hydrogen or helium. LmH ceases to bond covalently into H2 molecules under the extreme pressure, but rather begins to form an electron sea with other H nuclei in the manner of metallic bonding and begins to exhibit the properties of an electrical conductor. Helium likewise transitions into a fluid state under the most extreme pressures at the greatest depths and loses it's electron orbitals, forming an electron sea amidst its nuclei. Both transition into quantum superfluids losing all viscosity in these states.

As a matter of practicality, the diameter of a gas giant is generally measured at the mean altitude where the atmospheric pressure equals 1 atm. This corresponds to the mean surface pressure of Terra's atmosphere, which is used as a benchmark.

- Anything lying above this atmospheric pressure region is termed the Upper Atmosphere.

- Anything lying below this atmospheric pressure region is termed the Deep Atmosphere.

This definition of the surface is very arbitrary: a gas giant's atmospheric pressure varies greatly from region to region, and even the smallest gas giant will have many hundreds of kilometers of complex, stratified "upper" atmosphere above the measuring point.

- Terms such as diameter, surface area, volume, surface temperature and surface density effectively refer only to the outermost layer visible from space.

- The third digit of the "PBG" element of the Universal World Profile indicates how many gas giants and/or ice giants are present within the star system.

In the above diagrams, the Upper and Deep Atmosphere of the Gas Giant is generally composed of diatomic molecular Hydrogen and much smaller amounts of monatomic Helium gas. As one transitions into the Gas Giant's mantle regions, first the Hydrogen, and then eventually the Helium transitions to a liquid metallic state under degeneracy pressure. The Upper and Deep Atmosphere of the Ice Giant is generally composed of diatomic molecular Hydrogen and much smaller amounts of monatomic Helium gas with significant amounts of molecular methane. As one transitions into the Ice Giant's mantle regions, the composition transitions into predominantly water, ammonia, and methane ices that eventually phase transition into a supercritical water-ammonia ocean.

Gas Giant Life[edit]

It is possible for lifeforms (and even NILs) to originate on gas giants

- Lifeforms that have evolved on gas giants are called jovionoids.

Probable Planetary Orbit & Climate[edit]

Due to the mechanics of system formation, related to the distribution of material within the protoplanetary disk, gas giant worlds most commonly form within the outer regions of a star system, or more rarely within the habitable zone. They are usually found in those regions of the system.

- Occasionally, celestial mechanics and gravitational forces may cause a gas giant world to migrate within the star system, rearranging the orbits of other worlds and even causing them to be ejected from the system, becoming starless Rogue Worlds. Some migrate inward and a few, rather than rapidly burning up in the star's photosphere or being flung out of the system, instead settle into a stable orbital position very close to the star. These worlds become Hot Gas Giants, often referred to as Hot Jupiters or HGGs.

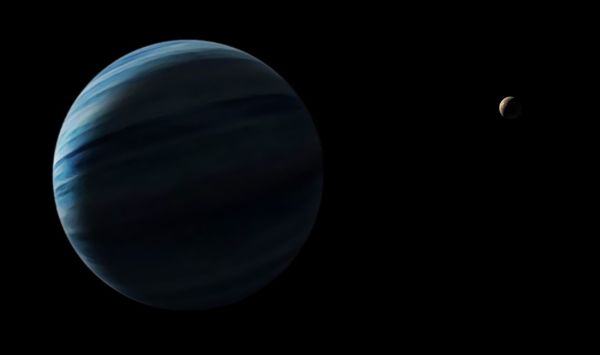

The color of a gas giant depends largely on its chemical components and the various compounds and substances that form within it; these stain the atmosphere. Colors typically include white, gray, and shades of blue, green, yellow, orange, brown, tan and red. Gas giants look very different if viewed in different spectra such as infrared. Gas giants are most commonly monochrome, mottled or banded. A Hot Jupiter may be incandescent.

The upper layers of a gas giant's atmosphere appear similar to the skies of a terrestrial world: the gas mixture is generally transparent, with vast banks of mountainous clouds divided by abyssal chasms and sporadically lit by the flashes of enormous bolts of lightning. The gas mixture becomes denser and more opaque with depth.

- Different chemicals and compounds may precipitate out of the atmosphere at different altitudes, temperatures and pressures. They manifest as fogs, rain, sleet, snow, or as heavier solids (typically ices, salts, or sands).

- Wind speeds within the upper atmospheric layers of a gas giant can exceed 600 kph: in some atmospheric layers the local windspeed may exceed the speed of sound. Different atmospheric layers have prevailing winds travelling in different directions: the convergence zones between different atmospheric layers may be extremely turbulent.

- Individual weather events, such as large storms, can cover millions of km² and last for decades or centuries.

Magnetosphere[edit]

Gas giants have strong magnetic fields, generated deep within their mantles and with strengths significantly higher at the poles than the equator. Their magnetic fields tend to balloon for millions of kilometers towards their star and taper into long tails that trail for billions of kilometers away from it, stretched out by the star's stellar wind, the constant energy and material streaming off of it

- Huge, spectacular auroras may be seen above the gas giant's polar regions.

- Near the planet, the magnetic fields trap swarms of charged particles and accelerate them to very high energies, creating intense radiation belts. It is not unusual for moons to orbit within radiation belts.

The electromagnetic storms generated by the magnetosphere produce a great deal of electromagnetic noise across a broad spectrum. This may seriously hamper sensor operations and communications.

- At times, gas giants can produce significantly more powerful signals than their parent stars.

History & Background (Dossier)[edit]

The Solomani sometimes refer to gas giants as a Jovian planet after the planet Jupiter in the Terra system.

Gas Giant Types[edit]

Gas Giant worlds most commonly form within the habitable zone and the outer system and are usually found in those regions. Ice Giants & Gas Giants can be broadly classified according to two primary classification schemes. The first classification scheme is based largely upon size, whereas the second, the Sudarsky Classification, is largely based upon temperature and the resultant chemical properties of the atmosphere. Note that the Sudarsky Classification scheme does not apply to Ice Giants, but to Gas Giants only.

Giant Planet Classification by Size[edit]

| Size Classification: Ice Giants / Gas Giants / Substellar Objects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| World Type | Abbrev | Zone | Remarks |

| Ice Giants | |||

| Gas Dwarf | GD | Habitable Zone | A type of small gas giant planet, with diameters ranging from 18,000 km to 50,000 km. A "Gas Dwarf" (sometimes referred to as a "mini-Neptune" or a "Transitional Planet") straddles the border between Pelagic terrestrial "Bigworlds" (i.e. Water worlds or Ocean worlds) and Ice Giants, in that they typically have a core comprised of deep layers of ice, rock or liquid oceans (made of water, ammonia, a mixture of both, or heavier volatiles), but otherwise have a thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. Gas Dwarfs and Ice Giants are similar in size and appearance, though Gas Dwarfs experience lower internal pressures. |

| Ice Giant | IG | Habitable Zone | A type of small gas giant planet with diameters typically ranging from 20,000 km to 60,000 km. Ice giants generally have similar sized cores to other type of gas giants and formed within the outer system, gathering material from the outer part of the protoplanetary disk.

They are primarily composed of molecular compounds of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur "ices" (often bonded with hydrogen in molecular arrangements), whereas hydrogen and helium make up only about 20% of their total mass (as compared to 90% in a true gas giant), mostly in the higher atmosphere region mixed with gases such as molecular methane. Under the extreme pressures and temperatures found deep within the world, these heavier elements and the complex compounds they form exist as supercritical fluids (typically ammonia and water "ices") and hot crystalline structures, and account for about two-thirds of the mass of the ice giant. These are referred to as exotic ices and give the world type its name. Fuel skimming is possible but requires at least 2-G of acceleration to regain orbit. (This is possible by overloading 1-G drives but not recommended). The "standard" ice giant is Neptune, in the Terra system. |

| Gas Giants | |||

| Small Gas Giant | SGG | Habitable Zone | (Sudarsky Class I - III). A type of gas giant, with diameters ranging from 20,000 km to 60,000 km. Small gas giants generally have similar sized cores to large gas giants and formed within the outer system, gathering material from the outer part of the protoplanetary disk. They are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium: during their formation they were unable to gather the vast amounts of materials necessary to enable them to develop into large gas giants or the relatively large amounts of volatiles characteristic of ice giants. Small gas giants and ice giants are similar in size and appearance.

Small gas giants experience lower internal pressures than large gas giants, though those pressures are still very extreme. Their interiors are intensely hot, with a dense but relatively shallow mantle composed of liquid hydrogen, a turbulent deep atmosphere filled with cloud layers composed of silicates and salts, and a transparent outer atmosphere that is generally far taller than those found on large gas giants. Fuel skimming is possible but requires at least 2-G of acceleration to regain orbit. (This is possible by overloading 1-G drives but not recommended). |

| Large Gas Giant | LGG | Habitable Zone | Sudarsky Class I - III. Gas giant planets composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, with diameters ranging from 60,000 km to around 200,000 km. They formed within the outer system, around stony or metal-rich cores which accumulated gases and volatiles from the outer part of the protoplanetary disk.

Large gas giants experience extremely high internal pressures. Their interiors are intensely hot, with a dense mantle around the core composed of metallic hydrogen (a degenerate material with similar properties to superdense armor) and liquid hydrogen, a turbulent layered deep atmosphere filled with clouds composed of salts and silicates, and a relatively shallow, largely transparent outer atmosphere where pressures drop below 1 standard atmosphere and eventually give way to the vacuum of space. There are no distinct layers within the world: the mantle transitions gradually into the deep atmosphere, which in turn gradually transitions into the outer atmosphere. Large gas giants have powerful weather systems and violent winds. They may have one or more gigantic world-sized storms that last for centuries. Fuel skimming is possible but requires more than 2-G of acceleration to regain orbit. (This is possible by overloading 2-G drives, but not recommended.) The "standard" large gas giant is Jupiter, in the Terra system. |

| Hot Gas Giant | HGG | Inner System | Sudarsky Class IV - V. Hot close gas giants orbit very close to their star and are relatively young in terms of stellar evolution: the energy streaming off of the star relentlessly strips away their atmospheres, reducing them to a dense near-vacuum core remnant (a "Cthonian world") within a billion or so years. The former atmosphere may exist as a sleet of ionised gases and more complex compounds, with a relatively high density compared to the normal interstellar medium, being carried back through the system and into interstellar space on the stellar wind.

The world forms, like other gas giants, within gas-rich regions of the outer part of the protoplanetary disk, but at some point the gas giant changes its orbital distance around the star. Most probably this migration is caused by the interactions of multiple large planetary bodies during the evolution of the system, but in some cases it may be due to disruption generated by the passing of a wandering star or very large rogue world. Some gas giant worlds migrate inward through their star system as a result of this cosmic reshuffling, eventually moving extremely close to the star. Some, rather than burning up in the star's photosphere or being slung out of the system, settle into a stable orbit. During their movement into the inner system, migrating gas giants may have cleared orbital positions of existing planetary bodies. Their gravitational influence may have shattered worlds and created planetoid belts, they may have shed their moons during their transit and these in turn may have settled into stable orbits around the star and become independent planets in their own right, or the gas giant may have "towed" former outer system worlds inward behind it. The extreme temperatures that Hot Gas Giants experience causes them to swell and become puffy: younger examples may be up to 400,000 km in diameter and may stream trails of hot gas from their boiling atmospheres. Their diameter steadily reduces as the stellar wind erodes their atmosphere away. A Hot Gas Giant that has had its entire atmospheric envelope stripped away, exposing a naked rocky or metallic core, is known as a Chthonian planet. Fuel skimming is possible but extremely hazardous in the very high temperatures and extreme weather conditions found on the world. Drive requirements depend on the remaining mass of the world: at least 2-G of acceleration is recommended to regain orbit. |

| Substellar Objects | |||

| Sub-brown Dwarf | SBD | Inner System | Class I Substellar Object (SSO): Sub-Brown dwarfs are massive gas worlds whose masses lie between Gas Giant planets and Brown Dwarfs. In many ways they are superficially indistinguishable from Large Gas Giants, the primary distinguishing characteristic being their method of formation and core composition: Whereas a Gas Giant forms via the accretion of a rocky core thru the planetary formation process and the gravitational retention of a massive atmospheric envelope of light elements such as hydrogen and helium, a Sub-brown dwarf forms thru the gravitational collapse of a nebular gas cloud in a manner similar to that of true Stars and Brown Dwarfs. Sub-brown dwarfs, however, ultimately lie below the minimum mass threshold of 13 MJ necessary to initiate deuterium fusion or any other kind of nuclear fusion within their cores. Some nomenclature proposes classifying Sub-brown dwarfs as "H-Type dwarfs".

Despite their higher mass, Sub-brown dwarfs diameters are not much larger than that of a Large Gas Giant: their high gravity physically contracts the world, causing electron degeneracy within the material that their cores are composed of (electrons fill the lowest quantum states, forming electron degenerate matter, similar to superdense armor). Generally speaking, even with increasing mass and gravity, a Sub-brown dwarf's diameter will increase very little in size. Fuel skimming is possible but hazardous in the conditions found on such worlds. Drive requirements depend on the mass of the world: considerably more than 2-G of acceleration is required to regain orbit around Sub-brown dwarfs (This may be possible by overloading 2-G drives, but is a highly risky procedure.) |

| Brown Dwarf | BD | Inner System | Class II Substellar Object (SSO): Brown dwarfs are massive gas worlds that lie between large planets and small stars. Brown dwarfs are so massive that they were able to ignite limited deuterium fusion within their cores during their formation, with the most massive being able to briefly maintain lithium fusion. They do not undergo the (light) hydrogen fusion of the proton-proton chain which marks true stars, however. As the quantity of deuterium and/or lithium within a typically star's composition is generally quite small, the initial period during which a Brown Dwarf undergoes core-fusion is relatively brief. Depending on their mass they may superficially resemble Hot Gas Giants or the smallest type M stars.

Brown dwarfs are classified into three broad types:

Despite their very high mass, brown dwarfs have small diameters and are not much larger than gas giants: their incredibly high gravity physically contracts the world, causing electron degeneracy within the material that their cores are are composed of (electrons fill the lowest quantum states, forming electron degenerate matter, similar to superdense armor). Generally speaking, even with increasing mass and gravity, a brown dwarf's diameter will increase very little in size (if at Fuel skimming is possible but extremely hazardous in the extreme conditions found on such worlds. Drive requirements depend on the mass of the world: at least 6-G of acceleration is required to regain orbit around Y Type dwarfs: being able to regain orbit around T Type and L Type dwarfs is beyond the capability of conventional drives. |

Sudarsky Classification (Gas Giants Only)[edit]

| Sudarsky Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Temperature | Chemistry | Remarks |

| Class I | < 150 K | Ammonia Clouds | The temperature range for a Class I Gas Giant requires either a cool star or a distant orbit. Superjovian Gas Giants would likely have sufficient internal heating to push them into a higher Class.

Jupiter & Saturn in the Sol system are classified as Class I Gas Giants. |

| Class II | < 250 K | Water Clouds | Appear as Class I Gas Giants, but with grayer and bluer bands amidst faded beige/tan. Superjovians in the outer system that radiate internal heating, as well as normal Jovians closer to the habitable zone fall into this category. Epsilon Eridani b (Ægir, in the in the Shulimik system) is a Class II Gas Giant. |

| Class III | 350-800 K | Cloudless | Appear as featureless blue globes due to Rayleigh scattering and methane absorption of red wavelengths. Class III Gas Giants lack cloud forming chemicals at these temperatures, except at the highest temperature-ranges, which may cause sulfides and chlorides to form some cirrus-like clouds. Class III Gas Giants are typically found in Inner Orbits. |

| Class IV | > 900 K | Alkalai Metals | First of the Hot Jupiter Classes. Carbon monoxide replaces methane in the atmosphere, with sodium and potassium in evidence in the upper atmosphere and cloud decks of silicates and iron in the deep atmosphere, with possible appearances of Titanium and Vanadium Oxides at the high end of the temperature scale. Class IV Gas Giants are typically bluish in color as Class III Gas Giants. |

| Class V | > 1400 K | Silicate Clouds | Second of the Hot Jupiter Classes. The hottest Gas Giants and somewhat cooler Gas Giants with gravity less than Jupiter form their silicates and iron cloud decks much higher up in the atmosphere. The world may glow red from thermal radiation, but this is usually overwhelmed by reflected light. Such worlds will usually be tinged with reddish overtones. |

Hot gas giants (Sudarsky Class IV-V), orbiting extremely close to their stars, may have a very exaggerated ovoid shape.

See also[edit]

Star systems

Universal world profile[edit]

- Main world

- Hex Number

- Universal World Profile

- Starport (Sp)

- Planetary Size (S)

- Atmosphere (A)

- Hydrosphere (H)

- Population (P)

- Government (G)

- Law Level (L)

- Tech Level (TL)

- Trade classification & Sophont Codes

- Importance Extension (Ix)

- Economic Extension (Ex)

- Cultural Extension (Cx)

- Nobility

- Bases

- Travel Zone

- PBG - Population, Belts, Giants

- P: Population Multiplier

- B: Belts

- G: Gas Giants

- Worlds

- Allegiance Code

- Stellar Data

References & Contributors (Sources)[edit]

| This page uses content from Wikipedia. The original article was at Gas_Giant. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. The text of Wikipedia is available under the Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. |

| This page uses content from Wikipedia. The original article was at Sudarsky's_gas_giant_classification. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. The text of Wikipedia is available under the Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. |

- Marc Miller. Twilight's Peak (Game Designers Workshop, 1980), .

- John Harshman, Marc Miller, Loren Wiseman. Library Data (A-M) (Game Designers Workshop, 1981), .

- Marc Miller. Imperial Encyclopedia (Game Designers Workshop, 1987), 24,88,93.

- Matthew Sprange. "Gas Giants, Planetoid, and other bodies." Journal of the Travellers' Aid Society volume 2 (2019): 80-85.

- Martin Dougherty. Referee's Handbook (Mongoose Publishing, 2021), 91.

- Ken Pick, Gas Giants at Freelance Traveller